Varicoceles and infertility vs the NHS

Varicoceles are the most common treatable cause of male infertility, but the NHS aren't doing enough.

A varicocele is seen as the most common treatable cause of male infertility. First described in the 1st Century AD by the Roman writer Celsus, Aulus Cornelius, however it was only linked to infertility in the 19th Century.

What is a varicocele?

A varicocele is an abnormal swelling of the pampiniform plexus, the network of veins that drain blood from the testicles to the left renal vein and vena cava. The swelling is thought to be caused by the backflow of blood due to faulty valves further up the body, which causes blood to pool in these veins due to gravity. In rare cases, they can be caused by the compression of the left renal vein near the kidney.

This, in turn, can cause heaviness and a dull ache, especially as the day progresses or after standing for long periods.

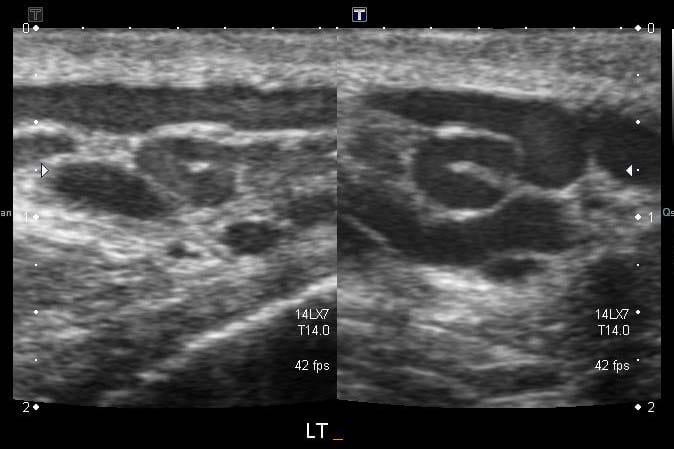

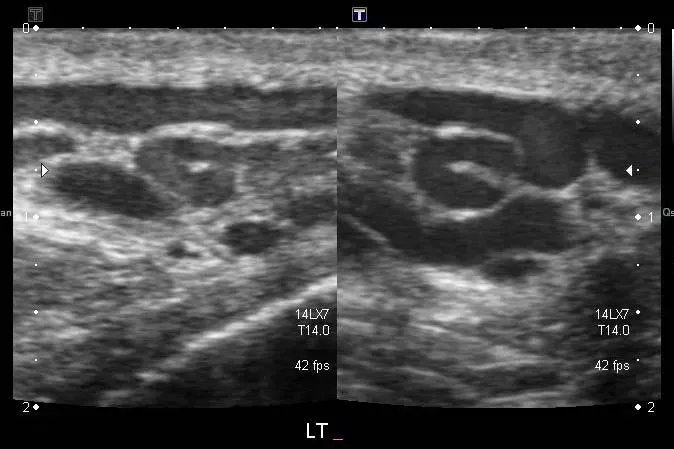

Pictured above: varicocele imaging conducted via ultrasound

How does this affect fertility?

Varicoceles cause blood to pool in the veins, which raises the internal temperature of the affected testicle(s). In order for spermatogenesis (production of sperm) to occur, the testicles need to remain around 4–6c cooler than the rest of the body, and if this temperature is not maintained, it damages sperm, and is thought to also damage the Leydig cells (that produce testosterone, the male primary sex hormone which is responsible for stimulating the production of sperm).

In detail, oxidative stress caused by the heat damages sperm DNA, which can cause DNA fragmentation (associated with miscarriages), and impairs sperm count, movement, and shape.

Male (in)fertility

In all infertility cases, men account for around 50%. Infertility affects around 5–10% of males in the UK. In men with primary infertility (trouble conceiving a first child), varicoceles are present in approximately 40% of them. Surely this links infertility and varicoceles? According to NICE (the National Institute for Clinical Excellence), men with varicoceles and infertility should not be referred for treatment (of a varicocele), and does not see varicocele treatment effective in solely improving fertility.

NICE has faced longstanding criticism of how cost-effectiveness influences treatment availability within the NHS. NICE is sponsored by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care.

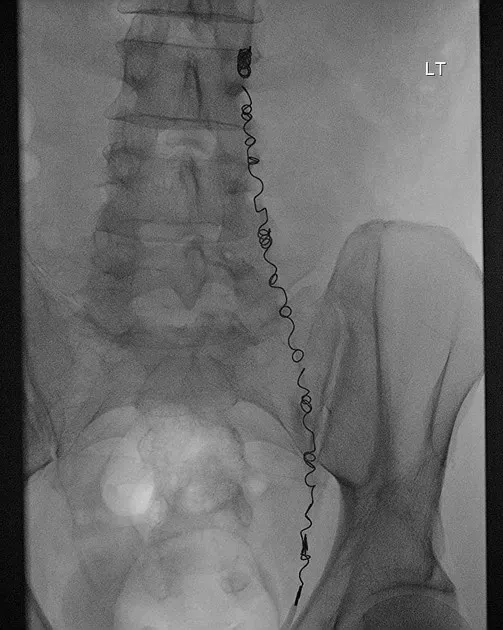

Studies show that varicocele treatment, whether by embolization (the use of foam or coils to block veins), or surgical ligation (the tying of veins) are effective in treating infertile men, and usually leads to improved semen parameters, sperm quality and testosterone levels.

Above: coils inserted via catheter down the spermatic vein to treat varicocele.

However, it is important to note that results vary due to differences in study designs. Nonetheless, infertile men with varicoceles should be offered treatment (after both partners have been assessed). Embolization is the most common treatment within the NHS, due to its short recovery time and low cost.

NICE prioritises live birth rates, not infertile men or semen quality, and only uses studies that are randomised and controlled, therefore believes evidence is insufficient due to the size of studies conducted and how most do not measure live birth outcomes. According to NICE, infertility affects 1 in 7 (around 14%) heterosexual couples in the UK.

Around the world

In contrast, the American Urological Association recommends treating palpable (visible) varicoceles in infertile men (with abnormal semen results). NHS guidance seems to focus more on cost-effectiveness over preventative intervention later.

The effect in adolescents and younger men

Varicoceles are usually noticed during puberty, which is thought to be because of the additional blood flow needed to produce testosterone and sperm.

Most younger men with a varicocele are often managed with waiting and reporting back if their discomfort increases or the varicocele enlarges. This isn’t enough.

Without running baseline tests, such as semen analysis, the functional impact of a varicocele cannot be accurately determined. Current studies show that a varicocele can cause testicular atrophy (shrinkage of (a) testicle), which significantly affects hormone production and semen quality. This damage usually happens when a varicocele is left to progress over time without treatment. Without early intervention and treatment, testicular atrophy is irreversible, which leads to further fertility issues.

Of course, testicular atrophy is detectable by an ultrasound, however most GPs will not refer for an ultrasound if a varicocele is diagnosed clinically, so there is usually no way to determine this. This reflects NICE guidance, that states diagnosis is usually clinical and only recommends (Doppler colour) ultrasounds in specific circumstances.

Fertility treatments

In England, IVF (in-vitro fertilisation) and ICSI (intracytoplasmic sperm injection) are widely used as assisted reproductive technologies (subject to local Integrated Care Board (ICB) policy).

In most areas, couples are funded for two or three (NICE guidance states that three full cycles should be funded; however for some ICBs this is unaffordable). These cycles are with or without the use of ICSI (which usually increases the chance of fertilisation with IVF).

Both IVF and ICSI bypass the male factor entirely and does not address underlying (male) causes such as varicoceles, meaning the male reproductive system stays untreated. This approach places significant physical and emotional strain on female partners — the effect of undergoing hormone stimulation, egg retrievals and embryo transfers.

If the male factor is not treated and the first rounds of IVF fail, a couple is usually forced to go private, where they can face costs of £3,000 — £7,000 per cycle.

For the NHS, treatment of a varicocele would be much cheaper and cost effective, however it’s not recognised enough in fertility care. The NHS should focus on treating the cause, rather than bypassing it and unnecessarily spending more money.

Is the NHS missing a preventable cause of infertility?

Despite varicoceles being a common and treatable cause of male infertility, current NICE and NHS practice fails to investigate male partners before progressing to techniques like IVF. This reflects the UK’s fertility care — where male fertility is frequently overlooked, and under-diagnosed, even though men contribute to around half of infertility cases.

Both primary and specialist care focus more on female reproductive health, and men can go many years without diagnosis or specialist referral. This leads to more expensive and invasive techniques being used — which effect both the couple and the NHS, instead of identifying the male factor and treating it.

For example, a recent article published by The Guardian shows how men frequently need to pay thousands for private treatment for a condition that could be treated by the NHS.

If NICE and the NHS took a more balanced approach — for example assessing both male and female partners and treating conditions instead of quickly progressing to more expensive treatments, will benefit couples and reduce the reliance on costly reproductive techniques.

This would align the NHS with the current and growing evidence and also address the economic and financial burden many couples face.

Sources (where applicable):

- 40% of men seeking primary fertility treatment have a varicocele — Revisiting the impact of varicocele and its treatments on male fertility, Reproductive Biomedicine Online.

- 50% of infertility cases caused by men — Male Infertility, StatPearls, American National Library of Medicine

- Testosterone levels and varicoceles (before/after treatment) — Balkan Medical Journal (via PubMed Central)

- Treatment of (palpable) varicocele in infertile men — American Urological Association

- Note: Sources for the number of IVF cycles funded by ICBs cannot be determined as varies between them, however, see NICE guidance here.

- Costs of private IVF is based on a number of providers researched during the writing of this article and the total cost is dependant on region.

- A number of other uncitable sources, such as personal experience are noted through this article. However, the best attempt has been made to ensure that all numerical statistics and clinical outcomes are cited.

This article does not diagnose a varicocele and isn’t medical advice. All sources are provided “as-is” and I lie no responsibility for them. If you are concerned about something, speak to a health professional.