The effect of "convinced" illness

Self diagnosed (convinced) illness is as high as it's ever been. But what are the effects of convinced illness?

In the present day, it's easier than it's ever been to research symptoms online, join forums or read stories about rare or chronic illness. For some, it relieves them and encourages them to get help and treat their illness early. For others, it can lead to a strong belief that something is wrong, despite little medical evidence or no test results that prove this. Conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia or mental health conditions like DID (Dissociative Identity Disorder) are most commonly prone to this, as they are poorly understood, lack clear tests and present with vague symptoms.

This line between genuine and "convinced" can be serious. For example, it can majorly affect a person's mental health (usually referred to as health anxiety).

Not all illnesses can be diagnosed with just a test. Some, like hyperthyroidism are difficult to diagnose but not impossible. Other illnesses, like fibromyalgia are clinically diagnosed based on the patient's view of their pain, as there is no definitive test to assess the condition (Bartlett, Matthew A. Fibromyalgia - history and examination. BMJ Best Practice. December 2023. Subscription required to view, Accessed 20th January 2026).

(Author note after publish: this does not suggest that fibromyalgia is an illegitimate illness, instead reflects how difficult it is to diagnose the condition when tests are limited.)

Between 5-10% of GP consultations are due to fatigue (NICE et al). Fatigue can be caused by many conditions, from less serious ones like stress, to more serious conditions like heart disease. This is exactly the same with symptoms like pain.

This makes it extremely difficult for clinicians to diagnose conditions with these symptoms.

The internet

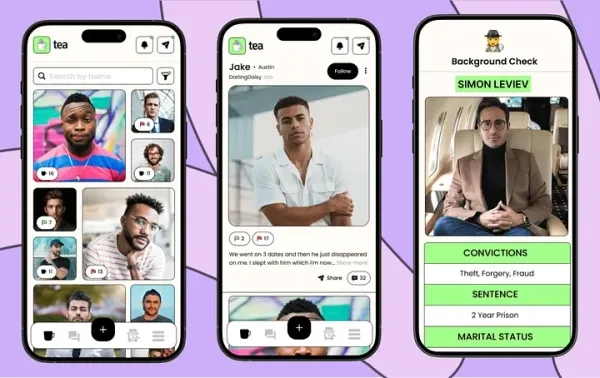

Many patients turn to the internet for answers about their health. Using the internet is not reliable, and full of misinformation. Nonetheless, in 2024, AXA Health reported that 48% of people they surveyed had self diagnosed using the internet. There are many valid reasons why patients self diagnose - whether they are unable to get an appointment, or concerned about long waiting lists for treatment or tests.

Patients may also feel embarrassed - an ongoing negative consequence of taboo topics in society. Not only does this worry patients about their potential diagnosis, but it also reduces the chance of early intervention for serious conditions.

However, over time, some patients may no longer believe they have an illness. Instead, they may claim very openly that they have this condition. This is not usually done by malicious intent, instead a gradual increase of belief. Once this happens, completely unrelated symptoms are usually blamed by that illness, which further reinforces their belief.

This belief can continue to increase anxiety and stress, with patients left worrying about whether they have "x condition", or "y condition", one life threatening, and the other harmless. Patients have been noted to continuously check their bodies for signs of illness and believing that normal sensations are signs of illness (2018, Tyrer, P. et al), and unnecessarily seek help from primary care. In the longer term, this may delay them receiving help for a legitimate condition.

The consequences

This thinking doesn't just have an effect on the patient themselves, but also wider healthcare and other patients. For example, it puts more pressure on an already overwhelmed GP appointment system and hospital referrals. This means that patients with actual symptoms and illnesses do not get seen quick enough, leading to potentially life threatening consequences.

In addition, tests and appointments are meant to reassure patients that their health is normal, however for many they do not provide reassurance. In some cases, repeated testing can reinforce the belief that something has been missed, and therefore beloeve that they need another test, reducing available appointments and costing the NHS more money.

Anxiety and uncertainty

Many patients who seek help from primary care wish for definitive answers about their condition or symptoms. This isn't always possible, as the patient may need to manage their symptoms, especially with conditions like fibromyalgia, where there is no treatment, which further puts pressure on patients.

In many patients, uncertainty can make their anxiety worse and cause them to stress further, wondering what will happen next or what is wrong with them further, continuing the cycle of (potentially unjustified) tests and examinations. This worry can once again cause patients to research on the internet further and feel like something serious has been missed, even if they are healthy and nothing is abnormal.

The effect on clinician trust

Health anxiety can strain the relationship between a patient and clinician. Patients may feel dismissed or ignored if they are told they are healthy. It is then difficult for a clinician to reassure them any further. In this case, the patient's trust may reduce and they may take alternate routes to seek validation or further reassurance.

Once again, patients may migrate to the internet and online communities, which can provide emotional support but also can reinforce their belief through shared stories and experiences.

So, where is the room for improvement?

NHS England already provides information pages for many symptoms and conditions on "Health A-Z", but they are generic articles that do not usually address specific or rare symptoms. They're usually updated every two years, but the NHS and NICE still fail to recognise modern guidance on newer conditions and complications from illnesses.

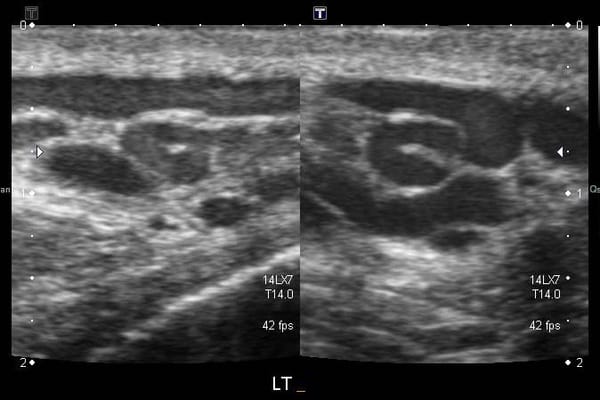

For example, the NHS does not have a page for varicoceles, an abnormal dilation of the spermatic veins, which can lead to infertility, low testosterone and testicular damage if left untreated. Varicoceles occur in roughly 15% of adolescent boys. (Sandlow, Jay Ira. Varicocele. BMJ Best Practice. July 2025. Subscription required to view, Accessed 21st January 2026 and Kang C, Punjani N, Lee RK, Li PS, Goldstein M. Effect of varicoceles on spermatogenesis.). This can lead patients wondering what is normal, particularly when trusted sources like the NHS provide limited information. Men's sexual health remains a taboo topic, which can discourage whether they get help or voice their concerns, similar to mental health.

Patients will naturally attempt to seek out as much information about their symptoms as they possibly can. If they can't receive this from trusted sources, they will move to untrusted sources, that could misinform them and increase their worries. Therefore, medical advice and information about health should be regulated. This means that government agencies should combat misinformation, to ensure that authors base their work on factual evidence, not personal experience or personal beliefs. This includes social media, where misinformation can spread like wildfire.

Another area for improvement is in primary care. Ten minute appointments are not long enough. Longer consultations can allow GPs to explore both physical and emotional symptoms, discuss a patient's mental health and help patients with plans that reduce visits or anxiety. Patients with health anxiety should also be referred into cognitive behavioural therapy to reassure and develop coping strategies. Early intervention may stop the persistent worrying and self diagnosis.

By improving patient communication and providing appropriate guidance in the first instance, this can stop the consistent "convinced" cycle of test after test and anxiety.

Patients are then encouraged to manage their health with confidence (not worries), so the healthcare system can focus on patients who truly need care.

What did you think of this article? Your feedback is anonymous and it'll be used to improve future articles.

Publisher's notice:

NICE - National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. They are funded by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. They are responsible for providing guidance to the NHS regarding treatments and conditions.

All sources have been cited where appropriate. A shorter cite may have been used to shorten the article. This article is not medical advice and you should always consult a medical professional if you are concerned about your health. The publisher and author bares no responsibility for the content(s) of this article, and any opinion statements may not accurately reflect the opinion of the publisher, but will reflect the author's opinion.

Notice on source(s) from BMJ Best Practice: BMJ Best Practice is a subscription service, therefore readers may not be able to access the content(s) linked. However, the publisher can confirm that the sources cited are correct on or before the date of publishing. BMJ Best Practice is provided by BMJ Publishing Group Limited.